Footnotes

[1] Timothy Sandefur, Permit Freedom, Goldwater Institute, February 15. 2017, goldwaterinstitute.org/article/permit-freedom/.

[2] Christina Sandefur, The Property Ownership Fairness Act: Protecting Private Property Rights, February 9, 2016 goldwaterinstitute.org/article/the-property-ownership-fairness-act-protecting-private-property-rights/

[3] “Why Price Controls Are So Uncontrollably Persistent,” The Economist (n.d.), https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2020/01/09/why-price-controls-are-so-uncontrollably-persistent.

[4] Murray N. Rothbard, “The Edict of Diocletian,” Faith and Freedom 1, no. 4 (March 1950): 11,

https://mises.org/library/edict-diocletian-case-study-price-controls-and-inflation.

[5] John W. Willis, “Short History of Rent Control Laws,” Cornell Law Review 36, no. 54 (1950), http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol36/iss1/3.

[6] D. K. Fetter, “The Home Front: Rent Control and the Rapid Wartime Increase in Home Ownership,” National Bureau of Economic Research, (Cambridge, MA, 2013).

[7] Thomas Sowell, “Shocking: The Right Not to Rent,” Kitsap Sun, July 10, 1999, https://products.kitsapsun.com/archive/1999/07-10/0002_thomas_sowell__shocking__the_righ.html.

[8] “Why Do House Prices Go Up?” Economy (n.d.), “https://www.ecnmy.org/learn/your-home/homes-housing-economy/why-do-house-prices-go-up/.

[9] Dennis Capozza, Patric Hendershott, Charlotte Mack & Christopher Mayer, “Determinants of Real House Price Dynamics,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 9262, October 2002, doi: 10.3386/w9262.

[10] Matt Levin and Ben Christopher, “Californians: Here’s Why Your Housing Costs Are So High,” CalMatters, August 21, 2017, https://calmatters.org/explainers/housing-costs-high-california/.

[11] Vanessa Brown Calder, “Zoning, Land-Use Planning, and Housing Affordability,” Cato Institute, October 31, 2017, https://www.cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/zoning-land-use-planning-housing-affordability.

[12] Michael Kelley, “Goldwater Institute Appeals Ruling in Mesa Impact Fees Case,” Goldwater Institute, November 8, 2014, https://www.goldwaterinstitute.org/article/goldwater-institute-appeals-ruling-in-mesa-impact/.

[13] Irvin Dawid, “California’s New ‘By-Right’ Housing Law: Will it Make a Difference?” Planetizen, October 5, 2017, https://www.planetizen.com/news/2017/10/95132-californias-new-right-housing-law-will-it-make-difference.

[14] Jenny Schuetz and Cecile Murray, “California Needs to Build More Apartments,” Brookings, The Brookings Institution, July 11, 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2019/07/10/california-needs-to-build-more-apartments/.

[15] Granger MacDonald, “Regulations, Fees Continue to Plague Home Construction,” The Hill, February 16, 2017, https://thehill.com/blogs/pundits-blog/economy-budget/319990-regulations-fees-continue-to-plague-home-construction.

[16] Emily Hamilton, “Four Regulations That Increase Housing Costs,” Mercatus Center, George Mason University, April 27, 2018, https://www.mercatus.org/expert_commentary/four-regulations-increase-housing-costs.

[17] John Phelan, “81% of Economists Agree That Rent Controls Are Bad Policy,” Center of the American Experiment, September 13, 2019, https://www.americanexperiment.org/2018/12/81-economists-agree-rent-controls-bad-policy/.

[18] Greg Rosalsky, “The Return of Rent Control” NPR, March 5, 2019, https://www.npr.org/sections/money/2019/03/05/700432258/the-return-of-rent-control

[19] Lisa Sturtevant, “The Impacts of Rent Control: A Research Review and Synthesis,” National Multi Housing Council, May 2018, https://www.nmhc.org/globalassets/knowledge-library/rent-control-literature-review-final2.pdf.

[20] John I. Gilderbloom and Lin Ye, “Thirty Years of Rent Control: A Survey of New Jersey Cities.” Journal of Urban Affairs 29, no. 2 (April 2007): 207–220, doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9906.2007.00334.x.

[21] Rebecca Diamond, Timothy McQuade & Franklin Qian, “The Effects of Rent Control Expansion on Tenants, Landlords, and Inequality: Evidence from San Francisco,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 24181, January 2018, doi: 10.3386/w24181.

[22] Dirk Early and Jon Phelps, “Rent Regulations’ Pricing Effect in the Uncontrolled Sector: An Empirical Investigation,” Journal of Housing Research 19, no. 2 (1999): 267–285.

[23] Dirk W. Early, “Rent Control, Rental Housing Supply, and the Distribution of Tenant Benefits,” Journal of Urban Economics 48, no. 2 (2000): 185–204, doi: 10.1006/juec.1999.2163.

[24] Choon Geol Moon and Janet G. Stotsky, J. G., “The Effect of Rent Control on Housing Quality Change: A Longitudinal Analysis,” Journal of Political Economy 101, no. 6 (1993): 1114–1148, doi: 10.1086/261917.

[25] Peter C. Rydell, Lance C. Barnett, Carol E. Hillestad, Michael Murray, Kevin Neels & Robert H. Sims, A RAND Note: The Impact of Rent Control on the Los Angeles Housing Market, The RAND Publication Series Document Number: N-1747-LA (Santa Monica: RAND Corporation, 1981).

[26] David P. Sims, “Out of Control: What Can We Learn from the end of Massachusetts Rent Control? Journal of Urban Economics 61, no. 1 (January 2007): 129–151, doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2006.06.004.

[27] Richard Ault and Richard Saba, “The Economic Effects of Long-Term Rent Control: The Case Of New York City,” The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 3, no. 1 (March 1990): 25–41, doi: 10.1007/bf00153704.

[28] Peter Linneman, “The Effect of Rent Control on the Distribution of Income Among New York City Renters,” Journal of Urban Economics 22, no. 1 (July 1987): 14–34, doi: 10.1016/0094-1190(87)90047-7.

[29] Carrie B. Reyes, “California’s Low Housing Elasticity: Trulia,” FT Journal, First Tuesday Journal, August 22, 2016, journal.firsttuesday.us/californias-low-housing-elasticity-trulia/54273/.

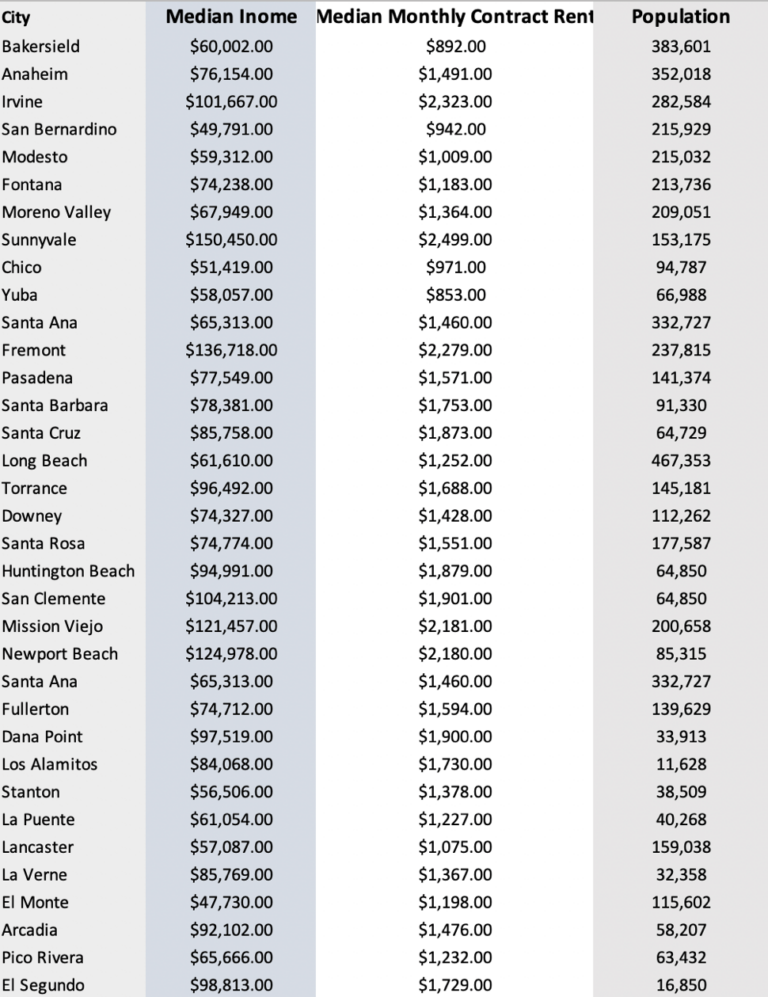

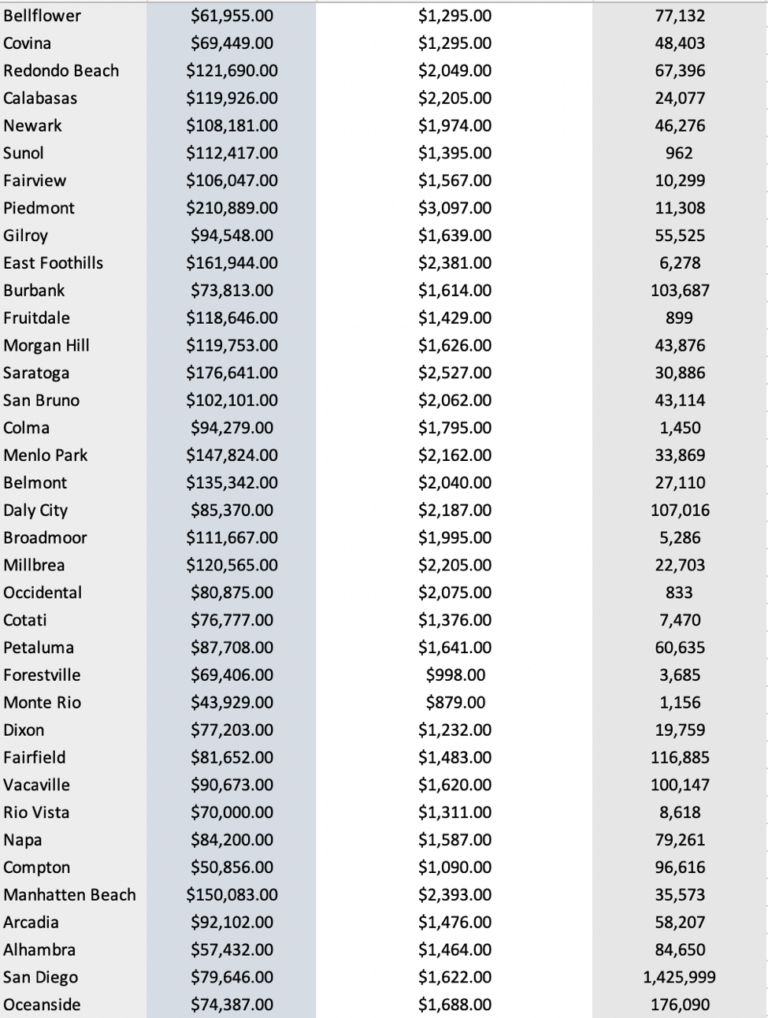

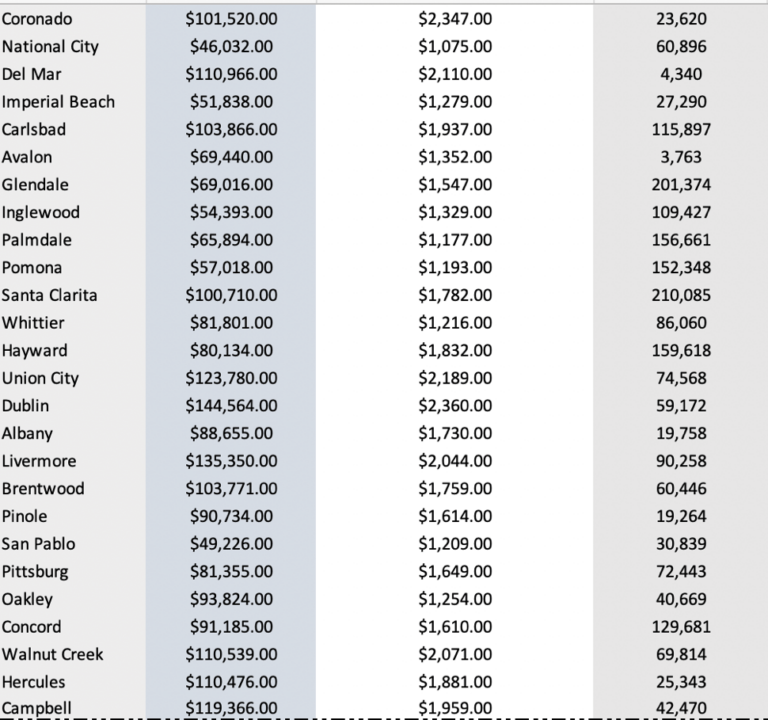

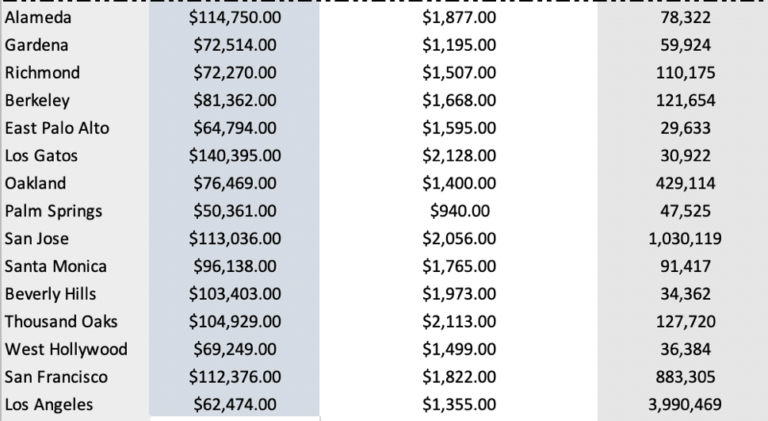

[30] U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey (n.d.), https://data.census.gov/cedsci/all?tid=ACSDP1Y2018.DP04&hidePreview=false.

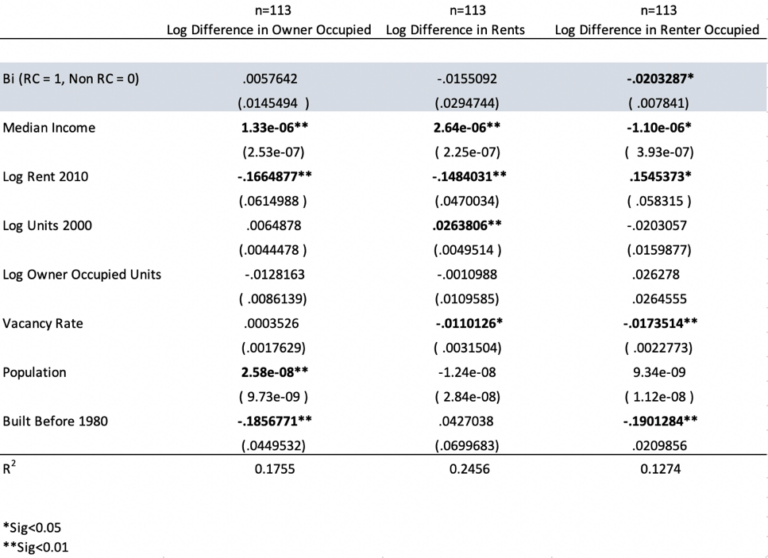

[31] U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States (n.d.), https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219.

[32] It is important to quickly note that this research focuses on associations and does not necessarily imply causal relationships. However, the research does point to potential causal relationships. More detailed and controlled research would be able to verify the validity of these relationships. This study also has a small sample size, so statistical error should also be considered before drawing concrete conclusions.

[33] Timothy Sandefur, “Permit Freedom,” February 15, 2017,

[34] Dana Berliner, et al, “The Land Use Labyrinth: Problems of Land Use Regulation and the Permitting Process,” Regulatory Transparency Project of the Federalist Society (January 8, 2020), regproject.org/paper/the-land-use-labyrinth-problems-of-land-use-regulation-and-the-permitting-process/.

[35] J.J. Dukeminier Jr., “Zoning for Aesthetic Objectives: A Reappraisal,” Law and Contemporary Problems 20, no. 2 (Spring 1955): 218., doi: 10.2307/1190326.

[36] Peter D. Kinder, “Not in My Backyard Phenomenon,” Brittanica, Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., October 9, 2019, www.britannica.com/topic/Not-in-My-Backyard-Phenomenon.

[37] Gretchen Blankinship and Andy Winkler, “Eliminating Land-Use Barriers to Build More Affordable Homes,” Bipartisan Policy Center, September 26, 2019, bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/eliminating-land-use-barriers-to-build-more-affordable-homes/.

[38] Christina Sandefur, The Property Ownership Fairness Act: Protecting Private Property Rights, February 9 2016, goldwaterinstitute.org/article/the-property-ownership-fairness-act-pro

[39] Annie Karnie, This gas station is a landmark?!, April 8, 2012, https://nypost.com/2012/04/08/this-gas-station-is-a-landmark/

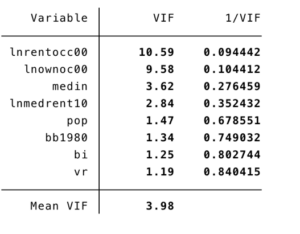

[40] Diamond, R. (2018, October 18). What does economic evidence tell us about the effects of rent control? Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/research/what-does-economic-evidence-tell-us-about-the-effects-of-rent-control/

[41] O’Brien, R. M. (2007). A Caution Regarding Rules of Thumb for Variance Inflation Factors. Quality & Quantity, 41(5), 673-690. doi:10.1007/s11135-006-9018-6