Everyone Deserves the Right to Try: Empowering the Terminally Ill to Take Control of their Treatment

October 7, 2014

In 2002, Kianna Karnes, a 41-year-old mother of four children, was diagnosed with kidney cancer.1 She was treated with interleukin-2, the only medication approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) at the time to treat her disease. When that treatment failed, her father began researching investigational medications, learning in 2004 that both Pfizer and Bayer were conducting clinical trials for new investigational medications to treat kidney cancer. Karnes was ineligible for the clinical trial because her cancer had previously spread to her brain. Although her brain tumors had been removed, she was still disqualified from joining the clinical trial, so her father sought expanded access for his daughter. Months passed before he was able to secure access for his daughter. He contacted Congressman Dan Burton’s (R-IN) office for assistance, and drew media coverage of Karnes’ struggle in the Wall Street Journal. On March 24, 2005, the FDA notified the family that it had approved a single-patient IND for Karnes. Tragically, it was too late—Kianna Karnes died the same day access was approved.2 Less than a year later, both drugs were given final FDA approval to treat advanced kidney cancer. Speaking after his daughter’s death, her father said, “I don’t know that either of these drugs would have saved Kianna’s life, but wouldn’t it be nice to give her a chance?”3

In the case of Kianna Karnes, she had a better chance than most patients at receiving expanded access. As her father explained, “Here is a case where her old man understood clinical trials. I knew about compassionate use; I had a friendship with a powerful member of Congress; I’ve got the Wall Street Journal behind me. But I still couldn’t save her life. Now, what about the thousands of people out there who don’t have these kinds of resources available to them?”4 To most patients, and many physicians outside of major institutions, the process of obtaining expanded access is excessively time-consuming and extremely difficult to navigate.

For patients suffering from terminal illnesses, the FDA is the arbiter of life and death. These patients, suffering from diseases ranging from ALS to Zellweger Syndrome, face little chance of recovery. For patients like Kianna, investigational medicines provide a glimmer of hope. The FDA, however, often stands between the patients and the treatments that may alleviate their symptoms or provide a cure. To access these treatments, patients must either go through a lengthy FDA exemption process or wait for the treatments to receive FDA approval, which can take a decade or more and cost hundreds of millions of dollars. Sadly, over half a million cancer patients and thousands of patients with other terminal illnesses die each year as the bureaucratic wheels at the FDA slowly turn.5

Patients should be free to exercise a basic freedom – attempting to preserve one’s own life. The burdens imposed on a terminal patient who fights to save his or her own life are a violation of personal liberty. Such people should have the option of accessing investigational drugs which have passed basic safety tests, provided there is a doctor’s recommendation, informed consent, and the willingness of the manufacturer of the medication to make such drugs available.

States should enact “Right to Try” measures to protect the fundamental right of people to try to save their own lives. Designed by the Goldwater Institute, this initiative would allow terminal patients access to investigational drugs that have completed basic safety testing, thereby dramatically reducing paperwork, wait times and bureaucracy, and, most importantly, potentially saving lives.

Introduction

Anna was only 13 years old when she died of an embryonal sarcoma, a rare form of liver cancer.6 Six months before she died, she had exhausted all conventional therapies, and her doctors informed the family there was nothing more they could do. Her parents were not willing to accept the news without a fight. They began researching experimental medications and soon discovered a number of investigational drugs in clinical testing to treat sarcomas like Anna’s. Anna’s age and advanced diagnosis, however, disqualified her from participating in the clinical trials, leaving the Tomalis family with one only option – asking the FDA for permission for Anna to try investigational drugs through an expanded access program – the single patient IND.

For months, the family sought approval for expanded access for their daughter. However, the process was difficult, uncertain, and time consuming. Anna’s mother said, “I came into this process so naïve, thinking that those of us who seek compassionate use of drugs actually get them. It was a shock to find out I had been seriously misled.”7 By the time the FDA finally granted access, it was too late. Anna died three weeks later, leaving her grieving family wondering whether Anna could have won her battle if she had been granted access sooner.

The FDA strictly controls which medications are available in the United States. Before a drug can be made available to the general public, it must undergo a lengthy and expensive clinical trial process to determine its safety and efficacy, which takes on average 10 to 15 years and over $800 million dollars to complete.8 Terminally ill patients can request exemptions, but the exemption process can take several months and requires doctors to complete paperwork that the FDA itself notes will require more than 100 hours to complete.9 Ultimately, the decision still rests with the FDA.

These bureaucratic impediments violate an individual’s fundamental right to try to save his own life. Unfortunately, the federal government has shown little interest in reforming the FDA as bills to reform the process for terminal patients have been introduced, but have never received a vote in Congress. State legislators, however, have the opportunity to protect their citizens’ right to try investigational medications by enacting Right to Try measures. These measures would ensure the right to protect one’s life by returning medical decisions where they belong – to patients and doctors.

History of FDA Regulations of Medications

Today, the FDA possesses wide regulatory authority to control which drugs may be sold within the United States. This regulatory authority was not granted in one fell swoop, but was the result of over a half century of legislation. During the twentieth century, the FDA evolved from a minor bureau with only 28 food and drug inspectors into a mammoth agency with a budget of nearly $4 billion.10

The Pure Food and Drug Act, passed in 1906, marked the beginning of federal regulation of drugs.11 The regulation prohibited the manufacture or sale of adulterated or misbranded foods and drugs which were produced in federal territory or transported across state lines.12 Enforcement of the act was given to the Bureau of Chemistry which was later renamed the FDA in 1927.13

Although there had been some earlier calls to require pre-market safety testing, it was due in large measure to the public outcry over the Elixir Sulfanilamide incident that Congress passed the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 (FDCA). The previous year, Elixir Sulfanilamide, a drug which had been used for years in tablet and powder form to treat streptococcal infections, was converted to a liquid form.14 The new liquid version of Elixir Sulfanilamide used diethylene glycol as a solvent, a poisonous compound.15 Tragically, the company was unaware of the solvent’s deadly effects.16 Within days of the first shipments, the drug began to claim lives across the country. Before the drug could be recalled by the manufacturer, more than 100 people had died.17 Congress responded by passing the FDCA, which for the first time granted the FDA the authority to require pre-market safety testing of all new drugs.18

After the enactment of the FDCA, the FDA began to require pre-market testing for drug safety, however pre-market testing for efficacy was not required until the 1960’s with the passage of the Kefauver-Harris Amendments.19 The Kefauver-Harris Amendments were enacted as a direct result of worldwide Thalidomide-caused birth defects. Although Thalidomide was sold in 46 countries, it was never approved for sale in the United States due to the FDA’s lingering safety concerns.20 While over 10,000 children worldwide were born with birth defects attributed to Thalidomide, only 17 of those children were born in the United States, where access to the drug was limited to those patients undergoing the FDA safety trial.21 The Kefauver-Harris Amendments drastically expanded the FDA’s regulatory authority by requiring drug manufacturers to prove efficacy prior to being approved for sale.22

This vast new granting of power was unwarranted. Thalidomide presented a safety problem (over which the FDA already had authority) – not an efficacy problem. As a result of the Kefauver-Harris Amendments, no drug could be sold within the United States until it had been deemed both safe and effective by the FDA.23

In response, the FDA designed a clinical trial process which is substantially the same practice still in place today. During the ensuing 50 years, everything in the medical world — from the way diseases are diagnosed and treated to the way medical records are kept — has been modernized, but the FDA continues to adhere to an approval process that is half a century old.

Unfortunately, by clinging to this dated process, the FDA creates substantial barriers which inhibit a company’s ability to bring new drugs to market in a timely fashion, even when those drugs have the potential to save lives.

Approving New Medications

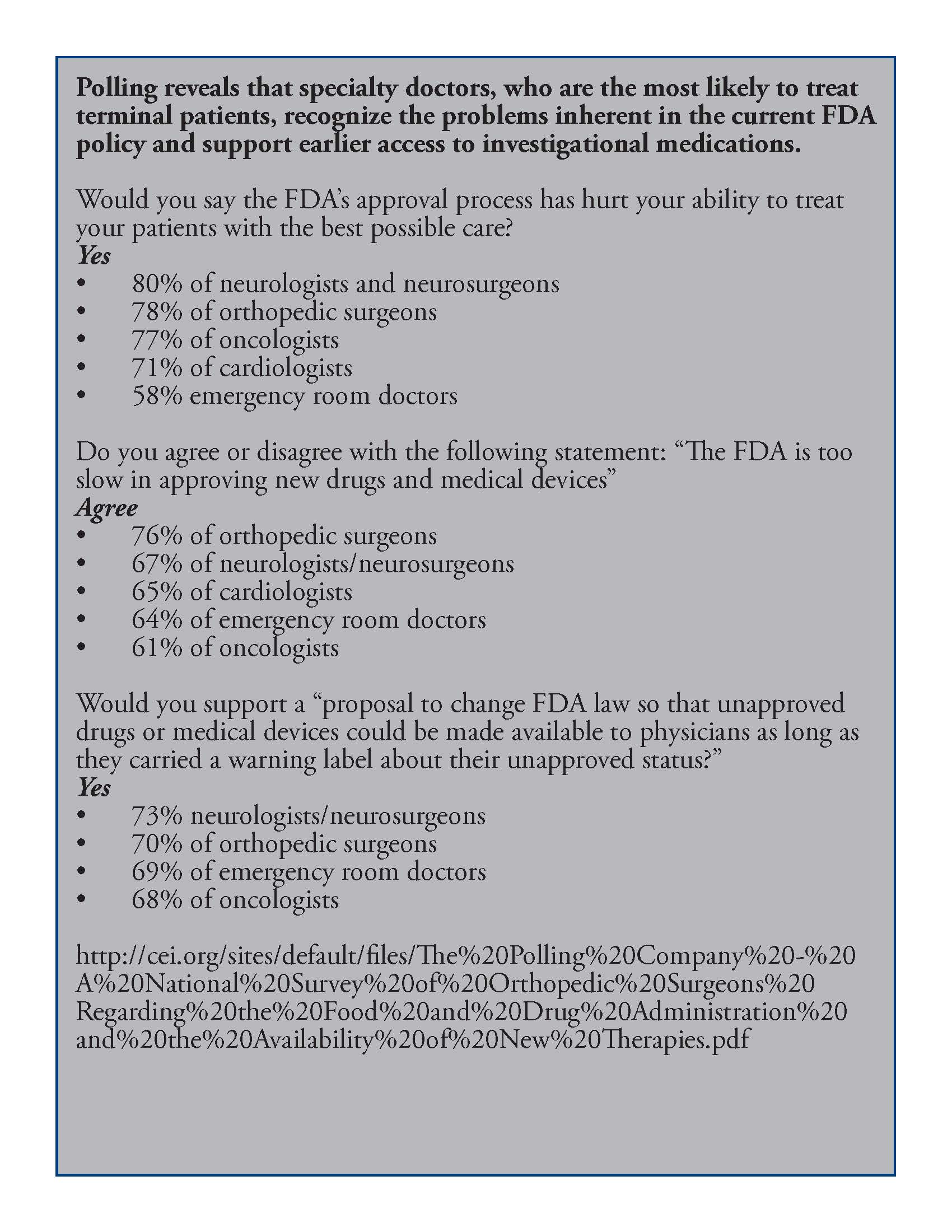

New drugs are vitally important to improving the lives and health of Americans. Between 1986 and 2000, new drugs were responsible for 40 percent of the total increase in life expectancy.24 Yet, the FDA’s clinical trial process remains lengthy and expensive. It takes, on average, more than a decade and $800 million dollars (though the cost often can exceed a billion dollars) to bring a new drug from the laboratory to the market.25 Polls show a clear majority of specialists believe the FDA clinical trial process is too slow and most report having been personally hindered in treating a patient due to the FDA approval process.26

The clinical trial process begins when a drug developer submits an Investigational New Drug Application (IND) to the FDA.27 The IND application includes all available data on the proposed investigational drug, including the results of any animal testing. In reviewing IND applications, the FDA seeks to ensure that the proposed trial does not expose patients to “unreasonable risk of harm.”28 Clinical trials then move ahead in three mandatory human testing phases.29 Phase I involves administering the investigational drug to a small group of 20 to 80 volunteers to test for toxicity and immediately observable side effects.30 The major emphasis of Phase I testing is safety. Over 60 percent of investigational drugs in Phase I testing are deemed safe enough to move on to Phase II.31

While safety continues to be evaluated, the main focus of Phase II is the drug’s effectiveness in treating the targeted disease or condition.32 Approximately one-third of the drugs in Phase II trials show enough evidence of efficacy to move on to Phase III.33

During Phase III, a much larger group of individuals receive the drug as the sponsor gathers additional evidence of efficacy by studying the drug’s effects in diverse populations, different dosages, and in combination with other medications. One rationale for Phase III is that as more patients are treated with the investigational drug, less common side effects are more likely to be discovered.34 During Phase III, the drug is administered to hundreds or even thousands of individuals.

Upon completion of Phase III, a drug sponsor may submit a New Drug Application (NDA) to the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) for review.35 The FDA then has 60 days to consider the NDA to determine if the application should move forward and filed for FDA review. The final review process can then take up to a year.36 To obtain final approval, the FDA requires that data amassed from the clinical trials indicate “substantial evidence” of both safety and effectiveness.37 According to the former head of the CDER, Janet Woodcock, the FDA approves approximately 75 percent of all filed NDAs.38

Clinical trials offer a way for patients to access investigational medications, but many of the sickest individuals are barred from participation. An estimated 97 percent of the sickest patients are ineligible for or otherwise lack access to clinical trials.39 Outside of participating in a clinical trial, patients have few options to access promising drugs.

The Era of Patient Activism and Demands for Change

Prior to the emergence of AIDS in the 1980’s, access to investigational drugs was limited almost exclusively to patients admitted into clinical trials.40 With the outbreak of AIDS, the FDA faced a group of patients who lacked any available treatment options.

AIDS was first identified by the Center for Disease Control in 1981 and spread rapidly among certain population groups.41 With an average of 10 years to bring a drug to market and no known treatments available, an AIDS diagnosis in the early 1980’s was akin to a death sentence.42 By April 1986, only 200 to 300 AIDS patients out of tens of thousands had been allowed to participate in clinical trials.43 An FDA official asserted that embarking on a wider scale clinical trial to provide expanded access would be “wasteful of resources.”44 Despite calls from AIDS patients desperate for any chance, the FDA clung to its assertion that it was simply protecting patients from potentially ineffective drugs. For these patients, confronted with a terminal diagnosis, questions of efficacy and side effects were irrelevant. One patient explained, “I know what the side effects of untreated AIDS are. Based on past experience, there’s a 75 percent chance I’ll be dead in two years.”45 These patients, who faced imminent death, began to demand access to drugs for which efficacy was unknown. This was the beginning of the movement for the recognition of terminal-patient rights.

FDA Expanded Access Programs

In response to AIDS patients’ demands for access to investigational drugs, the FDA began its first formal expanded access programs to allow limited access to patients outside the clinical-trial setting. While these new expanded access programs were a step forward for terminal patients, they proved largely ineffective at solving the problem of access. The promulgation of the 1987 expanded access regulations marked the first time the FDA had formalized an expanded access program to allow patients, under very limited circumstances, to access investigational drugs prior to final FDA approval. Expanded Access Programs (EAPs), including treatment INDs and later individual INDs, are often referred to colloquially as “compassionate use” programs.

The first formal expanded access program was the treatment investigational new drug (treatment IND) application process, which began in 1987.46 Under this program, a company sponsoring a clinical trial may submit a treatment IND application requesting FDA permission to allow specific groups of terminal patients to use the drug prior to FDA approval outside of the clinical trial.47 Treatment INDs are generally limited to investigational drugs that are in Phase III of clinical trials or have completed Phase III and are awaiting NDA approval. Although regulations permit granting a treatment IND during Phase II, such instances are rare.48 As the FDA describes it, for the agency to consider a treatment IND, the clinical trials must be “well underway, if not almost finished.”49 The FDA may approve the application if the clinical trials show promising evidence of the drug’s efficacy. If the treatment IND is approved, the sponsor of the investigational drug may begin providing access to a predefined patient group outside the ongoing trial setting.

While AIDS activist Martin Delaney called the new policy a “giant step for the sick and dying,” treatment INDs did not prove to be the boon that many patients hoped.50 Following the expanded access program, access to investigational drugs did not expand in a significant measure. By March 1990, the FDA had approved 18 treatment INDs for various conditions, which gave almost 20,000 patients who were otherwise ineligible for clinical trials access to investigational drugs.51 With tens of thousands of AIDS patients and over one and a half million cancer diagnoses each year, 20,000 was a minor improvement.52 In fact, from 1987 until 2002, the FDA approved only 44 treatment IND applications for conditions ranging from AIDS to chronic pain – an average of less than three per year.53

In 1997, 10 years after the first expanded access program, the FDA approved the individual, also called single-patient IND. Unlike treatment INDs, which grant access to a wider group of patients, the single-patient IND is designed to allow an individual patient who is otherwise ineligible for a clinical trial to obtain access to an investigational drug. An application for a single-patient IND may be submitted by either the patient’s doctor or the sponsor of the investigational drug.

Although the FDA had occasionally permitted individual patients to use investigational drugs outside of clinical trials, there were no formal rules governing how such grants were authorized prior to 1997. Because of concerns that the informal process was arbitrary and inconsistent, the issue was addressed as part of the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act (FDAMA) of 1997. FDAMA specifies that single-patient INDs are permissible only when all of the following conditions are met:

1.) The patient’s physician determines the patient has no comparable or satisfactory alternative therapy;

2.) the FDA determines there is sufficient evidence of safety and effectiveness to support the use of the investigational drug;

3.) the FDA determines that provision of the investigational drug will not interfere with the initiation, conduct, or completion of clinical investigations to support marketing approval; and

4.) the sponsor or clinical investigator submits information sufficient to satisfy the IND requirements.

Submission of an application for a single-patient IND is only permissible when the sponsor of the investigational drug has expressed willingness to supply the drug to the patient. If the sponsor is willing to provide access, the treating physician or the drug’s sponsor submits an IND application, an outline of the patient’s medical history, a proposed treatment plan, and a commitment to obtain informed consent from the patient and Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval.54

Although the FDA claims the paperwork burden placed on doctors who wish to apply for a single-patient IND on behalf of a patient is “non-labor intensive, straightforward, and appropriate,” the burden is actually quite extensive.55 The application itself reads, “the burden of time for this collection of information is estimated to average 100 hours per response, including the time to review instructions, search existing data sources, gather and maintain the data needed and complete and review the collection of information.”56 In rare situations, the request may be made over the phone, but the complex paperwork must still be completed soon after the initial verbal request.57 Although the FDA may believe the filing of an IND to be a small burden on physicians, members of the medical profession feel different. As Dr. Judy Stone, a physician with an independent practice explained, “Except perhaps for academic settings with an extensive infrastructure, INDs are incredibly burdensome, time-consuming, and expensive for an independent practitioner to obtain. They involve hours of paperwork. My office practice consisted of me and 1-1.5 secretaries. Who has time?”58

Once a single-patient IND application has been submitted, the FDA has 30 days to review the application.59 During this time, the FDA assesses risks and benefits posed to the patient (an analysis already performed by the treating physician), including whether there is enough evidence of the drug’s efficacy, and whether allowing access by a patient outside the clinical-trial setting would harm the on-going clinical trial. Although the FDA grants most single-patient INDs, the FDA retains the power to refuse an application in spite of the treating physician’s belief that the investigational drug represents the patient’s last hope.60

Burdens of the FDA’s Expanded Access Programs

“The decision for terminally ill patients to take an investigational drug should be between the physician and the patient, not government bureaucrats.” ~ Senator Sam Brownback (R-KS)

While the FDA is tasked with protecting the public from unsafe and ineffective medications, the agency’s approach is inappropriate in the context of terminally ill patients. The terminally ill face a much different risk-benefit analysis than the public at large. Patients who are not battling an immediately life-threatening illness are likely less risk-tolerant and more willing to wait for a proven cure, but terminal patients do not have the luxury of time. Many terminal patients who lack other treatment options may be willing, even eager, to try medications whose efficacy has not yet been established. Even the FDA has recognized that “for a person with a serious or life-threatening disease, who lacks a satisfactory therapy, a promising, but not yet fully evaluated product may represent the best available choice.”61

Despite this promising observation by the FDA, as of August 18, 2013, there were over 60,000 ongoing clinical trials, but only 210 ongoing expanded access trials.62 This number includes both treatment INDs and single-patient INDs. Reports from previous years show a similarly small number of patients gaining expanded access. In 2011, just shy of 1,200 patients received expanded access through either a single-patient or treatment IND.63 While the total had slightly increased from 1,014 patients in 2010, this is a very small number considering that, in that same year, there were 1,529,560 new cancer cases.64 In 2012, the number of patients granted expanded access dropped down to a mere 940.65 The onerous process the FDA requires a patient to go through to request expanded access contributes to the number being so low.

Despite the real possibility of death that is ever-present for terminal patients, the FDA persists in burdening a person’s right to try to save his own life by preventing access to investigational medications in three distinct ways. First, by requiring physicians to complete an IND for each request for single-patient expanded access, the FDA discourages doctors from even attempting to obtain access for their patients. Second, the FDA has unfettered authority to deny a terminal patient access to potentially life-saving medications for a variety of reasons, including nonmedical reasons. Third, the FDA’s requirement that all applications approved by the agency must then receive approval from an institutional review board further delays and inhibits access for patients in smaller and rural treatment centers. Together, these burdens create significant delays that can further endanger a person’s life.

The Burden of the IND Application

The requirement that physicians complete an IND for each request for single-patient expanded access is a significant hurdle standing between terminally ill patients and potentially life-saving medications. While some amount of paperwork may be reasonable, this form is so needlessly lengthy and complex that few doctors are willing or able to complete it.

Forty percent of cancer patients attempt to enroll in clinical trials.66 Many of these patients are turned away because they do not meet the stringent eligibility requirements or because they do not live near or have the ability to travel to a medical facility where the trial is being conducted.67 With more than a half-million deaths due to cancer every year in the United States and such a high level of interest from cancer patients in obtaining investigational medications, one would assume there would be a significant number of applications for expanded access to these medications every year. Yet, the average number of single-patient IND applications granted access to investigational medications for the last three years has been only 544. The burdensome IND application required by the FDA explains why the number is so low.

SOURCE: A National Survey of Orthopedic Surgeons Regarding the Food and Drug Administration and the Availability of New Therapies

The FDA is aware of the fact that the IND application requirement creates a serious impediment that discourages doctors from applying for single-patient expanded access. This is illustrated in the recent FDA attempt to require an IND application for fecal transplants.68

Such transplants are used to treat patients suffering from recurrent clostridium difficile infections. According to the Center for Disease Control, approximately 14,000 Americans die each year from clostridium difficile, but fecal transplants promise to greatly reduce that number.69 A recent study by the New England Journal of Medicine revealed that 81 percent of patients with a clostridium difficile infection were cured after the first transplant, and that number increases to 94 percent after a second transplant from a new donor.70 Despite the fact that clinicians have been providing this treatment with a very high success rate, the FDA announced in the spring of 2013 that henceforth physicians would need to seek an IND for each treatment.71 The outcry from physicians against this new requirement was swift.

Requiring an IND places a huge burden on doctors in terms of both time and cost – a burden that will result in fewer doctors who are willing to perform the procedure. As one gastroenterologist noted, “I’m already seeing that because of this requirement, a lot of doctors that were doing fecal transplants have either shut down or put their patients on hold.”72 Dr. Trevor Van Schooneveld of the University of Nebraska Medical Center had performed 20 fecal transplants since 2011, but after the FDA instituted the IND requirement, he had to delay treatment for three patients while he prepared and submitted an IND for each patient.73 Of course, not all doctors are able to put in the extensive time necessary to complete an IND, leading many to opt out of offering the procedure altogether.

Completion of an IND is complicated and time-consuming. When she was informed that the FDA would be requiring an IND for each transplant, Dr. Colleen Kelly, who had previous experience in completing INDs, began the process of filing an IND for the procedure. “I literally cleared my schedule in the office for two weeks of 12-hour days. The IND process is not ideal. There’s no ‘IND for Dummies.’ When you’re a doctor who wants to do this, it’s not a real straightforward process.”74 Furthermore, physicians are prohibited from submitting an individual patient access protocol to an existing IND for which the physician is not a sponsor, which means that a physician unfamiliar with the IND procedure cannot avail himself of a successful IND submitted by another physician.75 Dr. Kelly was not the only physician to take note of the IND burden. Another doctor complained of the increased cost, stating, “Just putting [an IND] together and carrying it out and managing data to the level of sophistication required by the FDA, just running it all costs a lot of money.”76 Patients have expressed their concerns as well. Barat McClain, whose clostridium difficile had been treated and cured with a transplant, said, “I fear many doctors will say, ‘It’s just a procedure I can’t afford to do. Time is money, and I can’t afford to spend my precious time filling out the damn forms.’”77

After receiving warnings from patients, physicians, and organizations such as the American Gastroenterological Association cautioning that requiring physicians to complete an IND for each transplant would result in the virtual elimination of this life-saving procedure, the FDA abruptly reversed course.78 On July 18, 2013, the agency released guidance for the transplants. The guidance was issued without prior public participation because such public participation was “not feasible or appropriate” as the subject dealt with “an urgent issue affecting patients with life-threatening infections.”79 In response to provider warnings that requiring an IND would essentially make fecal transplants largely unavailable, the FDA decided not to require an IND for each procedure provided there was adequate informed consent by the patient. The objective of the guidance was to “ensure widespread availability of FMT [fecal microbiota transplants].”80 In doing so, the FDA openly conceded that requiring individual INDs seriously inhibits, if not eviscerates, access to life-saving medical procedures.

FDA officials have stated that the agency wants patients with life-threatening diseases to have “early access to promising medical interventions.”81 Despite that oft-repeated statement, the FDA requires the completion of an IND that the agency has admitted makes certain procedures largely unavailable, especially since many doctors lack the time or expertise to deal with the burdensome application. In a recent survey, 60 percent of orthopedic surgeons said that the FDA hindered their ability to use “promising new drugs and medical devices.”82 In fact, studies show that among the reasons many doctors do not participate in clinical trials is the overly rigid protocols, concern about uncompensated staff time, lack of resources, and the burden of data management.83 Many of these concerns would be mitigated by eliminating the IND requirement.

The FDA’s Expansive Veto Power

Next, the FDA burdens the rights of terminal patients by claiming the authority to override both the will of the patient and the recommendation of a doctor by bureaucratic veto. The law allows the FDA to deny an individual request for expanded access if the agency believes there is insufficient evidence of either safety or efficacy, or if the agency determines that allowing access will interfere with clinical investigations.84 While on the surface this appears to be the worst of the three burdens, in reality, by making the IND so complicated and time consuming, most requests never even make it to this stage. Even so, it is troubling that when a doctor has taken the time to complete an IND and the company sponsoring the clinical trial has agreed to provide the patient access to the investigational drug, the FDA still has the power to deny the will of the patient, the advice of the doctor, and the charity of the sponsor. The FDA has acknowledged that people might question why, if a doctor already determined an investigational

drug represents the last and best hope for a terminal patient and the patient is willing to assume the risk, the FDA should have veto power.

Michael Friedman, the Lead Deputy Commissioner of the FDA, addressed this very question during congressional testimony, stating, “In a typical single-patient IND situation, especially those involving emergency IND requests, the patient’s physician may have only limited information about the investigational therapy being requested.”85

It is certainly true that information available during a clinical trial is limited, but the information is equally limited to patients enrolled in the ongoing clinical trial of the same investigational drug. For patients in the clinical trial process, the FDA deals with the lack of information not by banning access but by requiring informed consent to ensure that participants are aware of the possibility the drug could cause unknown side effects. Terminal patients should be afforded that same opportunity. As one father who fought to gain expanded access for his daughter explained, “If the only alternative is death, then for God’s sake, let ‘em have the drug.”86

According to FDA officials, “the Agency’s primary role in deciding whether to allow a single-patient IND to proceed is to determine whether use of the therapy in the particular patient involved is reasonable.”87 Although the FDA believes each request should be evaluated individually, the agency maintains there could be times when two people with the same life-threatening illness may receive different responses to IND applications, just as there may be circumstances which “make the risks acceptable for one patient, but not for another.”88 The reasonableness of a course of treatment, however, is not an objective fact that can be ascertained by a bureaucrat reviewing records – it is a deeply personal decision that should be made by the patient in consultation with his or her doctor and should not be second-guessed by government officials.

The FDA disagrees. As Patty Delaney, the former director of the FDA’s cancer liaison program explained in 2007, “the patient has a right to be heard, but in the end, it’s the data that matters. FDA opinions about safety and efficacy are always based on data.”89 If a trained medical doctor believes that, given the patient’s diagnosis and medical history, the patient’s best and perhaps only chance at life is to try an investigational medication and the sponsoring drug company is willing to supply the medication, the FDA should not have authority to overrule both the advice of the doctor and the wishes of the patient.

By the beginning of Phase II of a clinical trial, the FDA has already seen enough evidence of a drug’s safety to allow it to be tested on an expanded group of subjects. While the FDA talks at length about the potential risks expanded access patients would be exposed to, the risk to an individual patient outside the clinical trial is no greater than the risk the FDA is permitting patients inside the trial to take. No one expects investigational medications to be a panacea that will cure all those who use them, and indeed it is impossible to say how many will be helped by these medications. What can be said is the number who will be helped is unquestionably greater than zero. Patients and their families understand this, and most are realistic in their expectations. They are simply looking for a chance. As Jonathan Agin, a father of a young girl who was unable to obtain expanded access, explained in the Huffington Post, “We will never know whether the drugs we were not afforded access to could have helped Alexis. This is a heavy burden to shoulder in two simple words, ‘what if.’”90 That is a burden no parent should have to bear, yet it is a burden the FDA imposes.

If there is a chance for improvement and the patient is willing to accept the risk, which is no greater than the risk posed to any other patient enrolled in the ongoing clinical trial, government should not stand in the way. No government agency should have the authority to deny a terminal patient access to potentially life-saving medications, especially those already deemed safe enough for expanded human trials.

Perhaps the most troubling argument in favor of the FDA’s veto power is that the agency is always mindful of the effect expanded access may have on the clinical-trial process.91 As one FDA official put it, “An individual with a life-threatening and chronic illness for which there is no adequate remedy has a compelling case. As compelling as an individual case is, however, the cost of providing individual access cannot be to sacrifice the system that ultimately establishes whether therapies are safe and effective.”92 Mr. Friedman was referring to nonmedical reasons why the FDA may deny an IND application. In discussing why the agency might deny IND requests, the FDA recently noted that the “FDA could also have become aware, since authorizing previous requests for access, that access is impeding the clinical development of the drug and, on that ground, deny further requests for access.”93 The practical result is that a person who does not qualify for the clinical trial of an investigational drug could be denied access simply because there are not enough participants enrolled in the trial.

The FDA is concerned that allowing wider access to investigational medications outside the clinical trial setting will create a lack of test subjects who are willing to join a clinical trial, because in clinical trials some patients receive placebos or already approved medications instead of the investigational drug.94 The agency argues that freer access to such medications would discourage enrollment in the double blind clinical trials and ultimately harm scientific understanding of the medications. Therefore, the FDA puts protection of the clinical-trial process above the lives of terminally ill patients.

Beyond the lack of humanity inherent in this policy, there are additional flaws to the FDA’s position. Experimental medications designed to treat terminal illnesses are only a subset of the drugs undergoing clinical trials.The FDA’s position makes the assumption that the current clinical trial process, complete with the double blind studies, is the only sound way to test new medications. However, many scholars and even the former Director of the FDA, Andrew von Eschenbach, have urged alternatives to the current clinical trial process. 97 Nevertheless, the agency continues to place its outdated processes above all other concerns.

The Inequity of IRB Review Requirement

An additional way in which the FDA burdens the rights of terminal patients is to require that even when the agency grants access, the patient’s treatment must await review by an IRB.

An IRB is an independent board, often affiliated with a major medical or research institutions that must be registered with the FDA. An IRB is composed of at least five individuals with varied backgrounds, who review all IND applications for the purpose of protecting the welfare of human subjects undergoing clinical trials.98 IRB review is required for all IND applications before treatment may begin.99

IND applications for single-patient use are subject to “full IRB review.” Full IRB review means that the IND must be considered at a convened meeting at which a majority of the IRB members are present, including at least one member whose primary concerns are in nonscientific areas.100 To be allowed to proceed to treatment, the IND must be approved by a majority vote of the members present at the meeting.101 Although some IRBs at major academic institutions meet on a weekly basis, many IRBs meet only once a month. This can cause additional delays for a patient seeking the use of investigational medications, as treatment cannot begin before full IRB approval has been granted.

Additionally, the requirement for full IRB review creates a barrier for patients located in rural regions or who are being treated at smaller hospitals. Most IRBs are located at major academic research institutions and large hospitals, many of which prioritize the review of applications originating from within their own institution over outside applications. The FDA is aware of this barrier and in October of 2011 asked HHS’s Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Human Research Protection (SACHRP) to study the issue.102 The report generated by SACHRP stated that “substantial barriers” exist that inhibit access to investigational drugs and that these barriers are “exacerbated for physicians and patients outside of an institutional setting” in large part because of the requirement of full IRB review.103 Thus, the practical result of the IRB requirement is that patients in rural areas or who otherwise lack access to large medical institutions will, in many cases, lack the opportunity to obtain expanded access to investigational medications. The American Pharmacists Association describes the requirement of full IRB review as “prohibitively costly” and “burdensome,” and asserts its firmly held belief that the requirement “creates an impossible and undue burden on medical doctors treating individual patients in a community clinical setting.”104

The FDA’s requirement for full IRB review of all applications for single-patient INDs delays and limits access to investigational medications. The FDA itself recently noted that the agency “is aware of concerns that this requirement for full IRB review may deter individual patient access to investigational drugs for treatment use,” especially for patients “in settings in which IRB review is not readily accessible (e.g., healthcare settings that do not have IRBs).”105

Bureaucratic Delays Endanger Lives

The FDA’s long, costly, and burdensome process makes it difficult for patients to get the medications that may save their lives. Take the case of Everett Davis. At the age of 17, he was diagnosed with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH).106 The disease caused the formation of major blood clots and caused his kidneys to fail. For two years, his condition escalated until his hematologist was convinced his only chance for survival was an investigational drug called Soliris. After Davis and his family made countless calls to lawmakers to seek assistance in obtaining access to Soliris, Davis was eventually granted expanded access. The drug was so successful in improving his condition that within weeks Davis was approved for the transplant list that had previously been denied him. Luckily for Davis, his expanded access approval “came at the exact right moment” and the medication followed by the transplant saved his life.107 Sadly, many are not as fortunate.

Dr. Mark Puder of Boston Children’s Hospital has spent years treating infants who have fatal liver disease using a promising investigational medication called Omegaven.108 The FDA has permitted the medication to be given to patients through an expanded access program. A former FDA official, Dr. Timothy Cote, argues that the FDA’s expanded access application process is appropriate even in cases such as this where an infant is facing death.109 But a bureaucratic delay of weeks or months can mean the difference between life and death. As Dr. Puder explained, “The problem with this disease is it’s so rapidly progressive that you may lose the time to be able to rescue them. So, if their liver disease is bad at two months, and then it’s at four months now, you’ve hit a point where there’s a point of no return.”110

Patients and their families should not have to wait for bureaucratic whims to turn in their favor. When patients are facing terminal diseases, every day counts. Each extra day that it takes a doctor to fill out copious amounts of administrative paperwork, a bureaucrat to review an application, or to get on the schedule for an IRB, brings the patient a day closer to death and gives the possibly life-saving medications less time to work. Such procedural delays and hurdles threaten the lives of patients and should not be tolerated. We must move to protect the right of patients to access potentially life-saving medications.

Resisting Change

The FDA is extremely sensitive to the fact that every time it approves a new medication, the agency puts its reputation and power at risk. If the medication should later prove dangerous, the FDA will come under intense scrutiny from the media and Congress. In contrast, if the FDA is slow to approve a new medication, insisting upon more and more testing, the risk of scrutiny is much lower. This makes the distinction between the FDA committing a type one versus a type two error very important.

A type one error occurs when the agency approves a medication that is later discovered to produce serious side effects. In the case of a type one error, victims are clearly identifiable and visible to both the media and lawmakers. While the FDA can take corrective action, the damage to the agency’s reputation will have already been done as it faces media and legal scrutiny. Dr. Henry Miller, the founding director of the FDA’s Office of Biotechnology, illustrated the deep-seated fear the agency has of these type one errors. Dr. Miller described an instance in which he possessed reams of data detailing both the efficacy and safety of a new drug only to have his supervisor hedge on the approval after two and a half years of clinical trials, stating, “If anything goes wrong, think how bad it will look that we approved the drug so quickly.”111

A type two error occurs when the agency moves slowly and delays approving a beneficial medication. Although a type two error will result in needless deaths as patients await approval of the medication, the victims are largely unidentifiable. Without identifiable victims to be paraded in front of the cameras or a congressional committee, the danger to the FDA’s reputation is significantly less.

As underscored by Dr. Miller, the FDA is aware of the comparative danger to its reputation posed by type one and type two errors. The agency’s sensitivity to this issue is clearly reflected in the statements of former FDA Commissioner Alexander Schmidt who noted “in all our FDA history, we are unable to find a single instance where a Congressional committee investigated the failure of the FDA to approve a new drug. But the times when hearings have been held to criticize our approval of a new drug have been so frequent that we have not been able to count them.”112

Legislators Must Act to Protect Patients

“The decision on what course of action to take is the patient’s. After given the facts, if someone with a life-threatening or terminal illness wants to seek treatments that may offer a cure or slowdown in the progression of disease, then Federal agencies and red tape should not stand in their way.” ~ Congressman Dan Burton (R-CA)113

The delays and denials, which are inherent in the FDA’s current expanded access policy, have prompted recent attempts at the federal level to broaden access for terminal patients. Since 2008, four such bills have been introduced in Congress.114 Although these bills all had bi-partisan sponsors, none received a vote in committee, let alone a floor vote.

Despite such federal inaction, there is no right more basic than the right of the individual to protect his or her own life. The law recognizes this natural right by acknowledging a person’s right to self-defense. Individuals have the right to defend their lives. Through the lengthy approval process, the government has effectively denied the individual’s right to try to preserve his or her own life.

To protect the rights of patients with immediately life-threatening conditions, states should pass “Right to Try” legislation. Right to Try declares that the right of a terminal patient to access available investigational medications, devices, or biological products is a fundamental right and prohibits any government or government agent from interfering with that right.115

The Right to Try model legislation (Appendix A) designed by the Goldwater Institute is narrowly tailored and addresses many of the concerns that the FDA and others have expressed. To address the legitimate government interest of protecting the lives of citizens, Right to Try only allows access to medications that have passed basic safety testing (Phase I).116 Further, this legislation does not allow unfettered access to such medications after Phase I. It is limited to investigational medications for terminal patients who have exhausted other available treatments.117 Finally, the investigational medications are only available to patients under Right to Try if the sponsoring company chooses to make them available.118

Simply stated, Right to Try allows a patient to access investigational medications that have passed basic safety tests without interference by the government when the following conditions are met:119

1.) The patient has been diagnosed with a terminal disease;120

2.) the patient has considered all available treatment options;121

3.) the patient’s doctor has recommended that the investigational drug, device, or biological product represents the patient’s best chance at survival;122

4.) the patient or the patient’s guardian has provided informed consent;123 and

5.) the sponsoring company chooses to make the investigational drug available to patients outside the clinical trial.124

For patients suffering from conditions for which there is no approved known cure, the FDA’s traditional role of protecting patients from drugs and devices that have not yet proven effective has little meaning. These medications have already been deemed safe enough to enlarge the group of patients involved in the clinical trial to several hundred or even several thousand individuals. The requirement for informed consent ensures that terminal patients considering this option are fully aware of the risks involved. Moreover, allowing earlier access to investigational medications with informed consent is supported by the medical community. Recent studies show that a clear majority of specialists, including neurologists, oncologists, orthopedic surgeons, and emergency-room doctors support making investigational drugs available prior to full FDA approval.125 Further, the Right to Try initiative allows the company producing the investigational medication or device to determine whether it will be made available.126 If a company does not wish to make a medication available due to lack of adequate inventory, fear of liability, or any other reason, the company is not compelled to do so. Furthermore, insurance companies are not compelled to provide coverage for investigational medications.127 Thus, Right to Try protects a patient’s right to medical autonomy without infringing on a company’s rights.

Constitutional Right to Medical Autonomy

It has long been established that the U.S. Constitution creates a floor of protection for individual rights – not a ceiling. States can and do provide additional and enhanced protections for individuals. For example, several states provide greater protections for speech or privacy than the U.S. Constitution does.

Additionally, the U.S. Supreme Court has recognized a series of fundamental rights protected by the Due Process Clause. These constitutionally protected rights include the right to marry, to use contraceptive medications, to live with one’s family, and to teach children a foreign language.128 Among the recognized fundamental rights, the Supreme Court has recognized several fundamental liberty interests in the area of medical autonomy. The right of a patient to control his own medical treatment has been a component of many due process cases, with the Supreme Court noting the existence of the “right to care for one’s health and person.”129 Although the right of terminal patients to access investigational medications has not yet been recognized by the Supreme Court, it is consistent with and can be supported by existing precedent.

If Right to Try is upheld, the government would be restricted from placing excessive regulatory requirements on terminal patients seeking access to investigational medications. The result is that the FDA would not be able to prevent a terminally ill patient who met the stated criteria from accessing investigational medications. Likewise, other procedural burdens such as the IND application and IRB review requirement could be deemed undue burdens and either eliminated or drastically curtailed.

The concept of ordered liberty cannot include allowing a government agency to promulgate and enforce regulations that impair an individual’s health or cause death by denying or delaying access to potentially life-saving medications. The way in which the FDA currently regulates access to investigational medications may be rational for non-terminal patients, but its application to terminal patients, who lack other treatment options, is not. Preventing such a patient from accessing a potentially life-saving medication will, without question, result in the fulfillment of the diagnosis — death.

Without state action, terminal patients are at the mercy of a federal bureaucracy that can literally cause death by delays, denials, and unnecessary procedural requirements.

Conclusion

From her sickbed, Edie Bacon wrote of the travails a terminal patient faces and made a final plea for the only medication that might save her. “The government wants proof of efficacy before it will allow me to take this drug outside of an approved trial. But the ‘proof’ is years away, and I need the drug now. It’s safe. It might work. Johnson & Johnson would let me have it if they could do so without the threat of a government hassle. But they’re so caught up in the FDA web that the life of an individual patient has no importance whatsoever. Without ET 743, I’m a dead woman walking. Five kids are going to wonder why they’re left without a mother. Won’t somebody help me get this drug?”130 Edie died two years later, but there are thousands of patients who face this same battle every day – patients who have to make the same pleas that Edie did for a chance to try to protect their own lives.

Such pleas should anger anyone who believes in the concept of personal liberty. No free person should have to come to the government as a supplicant to beg for a right to try to save his or her own life. In a country dedicated to the idea that all people have certain “unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness,” no government official should have the power to deny a person’s last chance at all three – life, liberty, and happiness.131 Yet that is the power the FDA wields today. States should challenge this regulatory authority by passing Right to Try and returning medical decision making back to the rightful hands of patients and doctors.

Read the full PDF here

References

Right to Try model legislation

Get Connected to Goldwater

Sign up for the latest news, event updates, and more.

More on this issue

Recommended Blogs

Donate Now

Help all Americans live freer, happier lives. Join the Goldwater Institute as we defend and strengthen freedom in all 50 states.

Donate NowSince 1988, the Goldwater Institute has been in the liberty business — defending and promoting freedom, and achieving more than 400 victories in all 50 states. Donate today to help support our mission.

We Protect Your Rights

Our attorneys defend individual rights and protect those who cannot protect themselves.

Need Help? Submit a case.